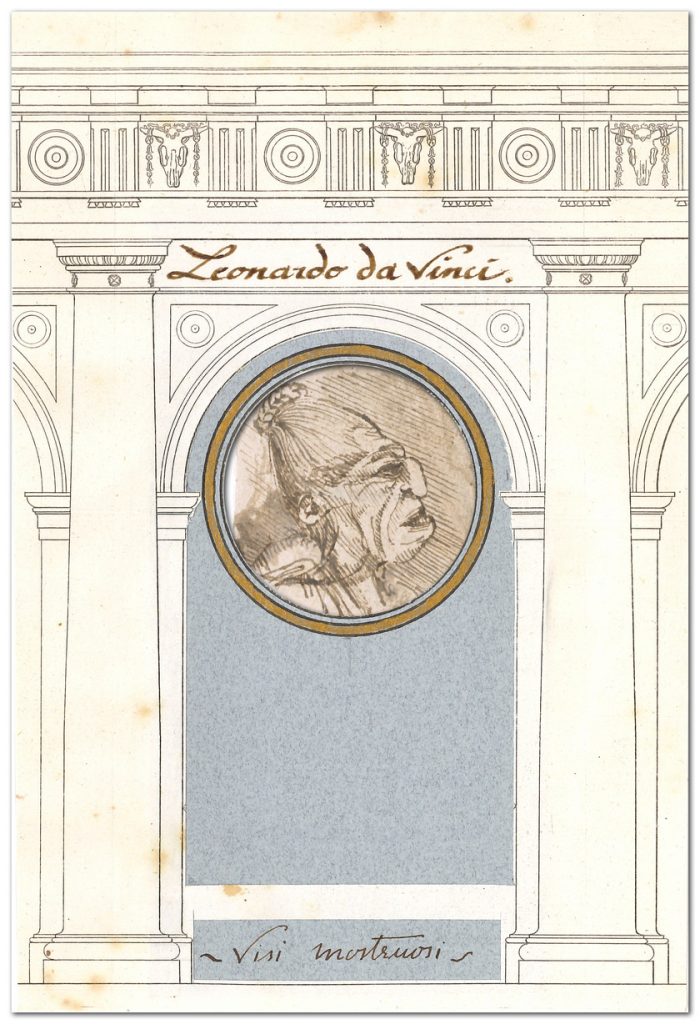

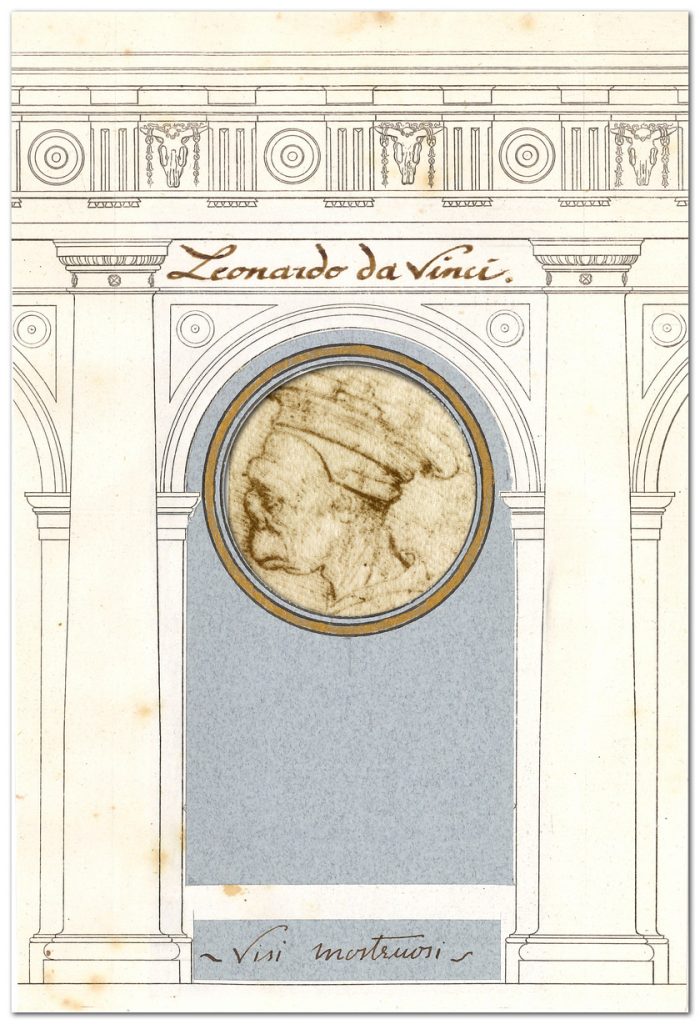

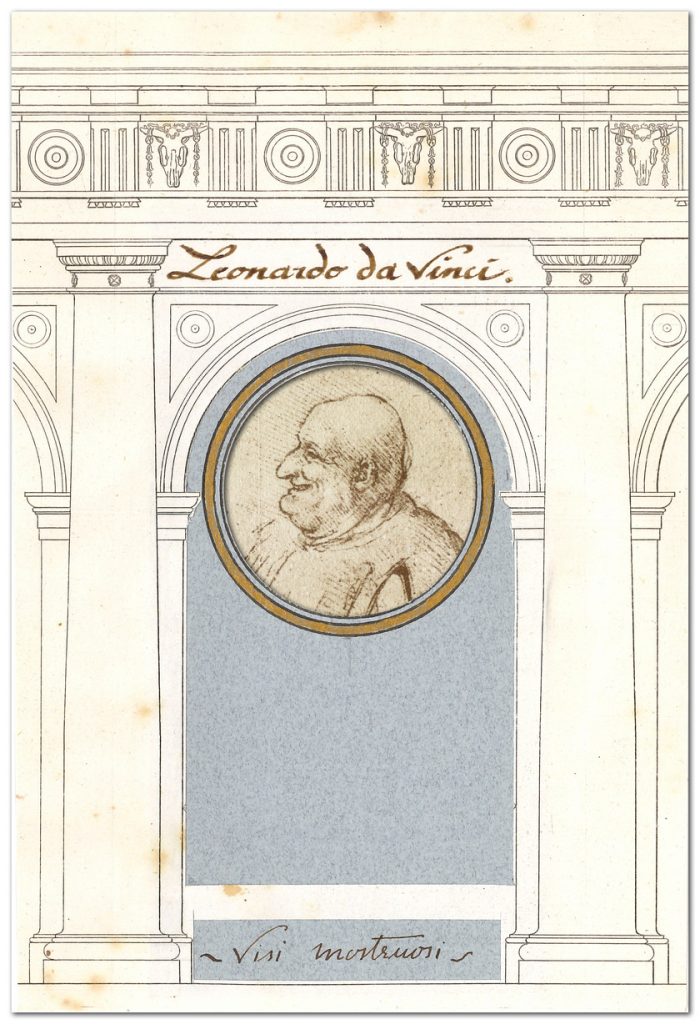

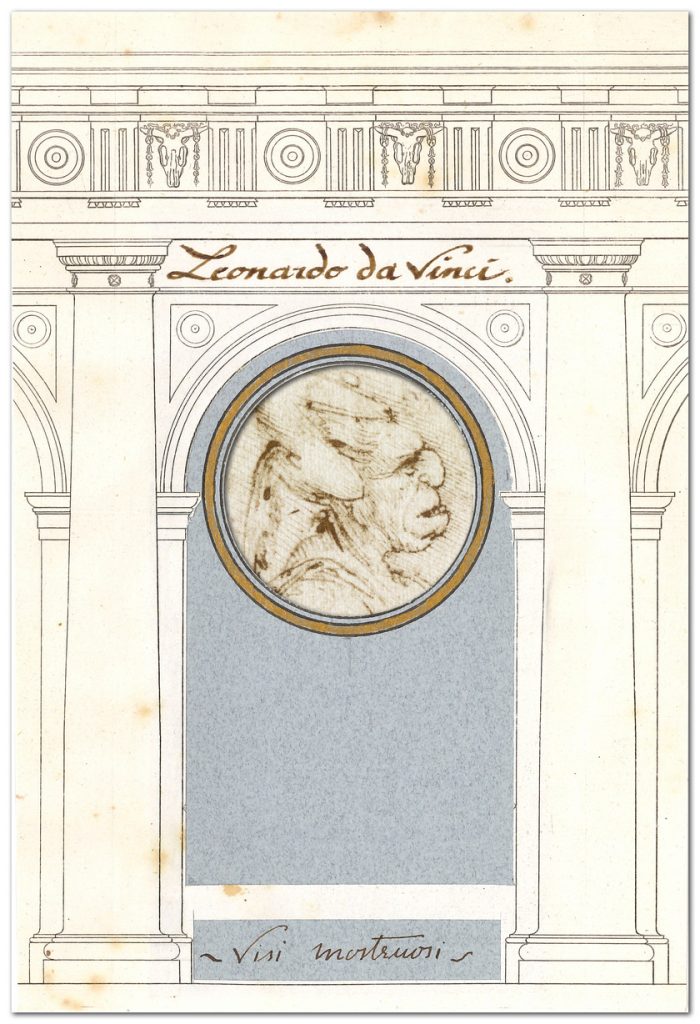

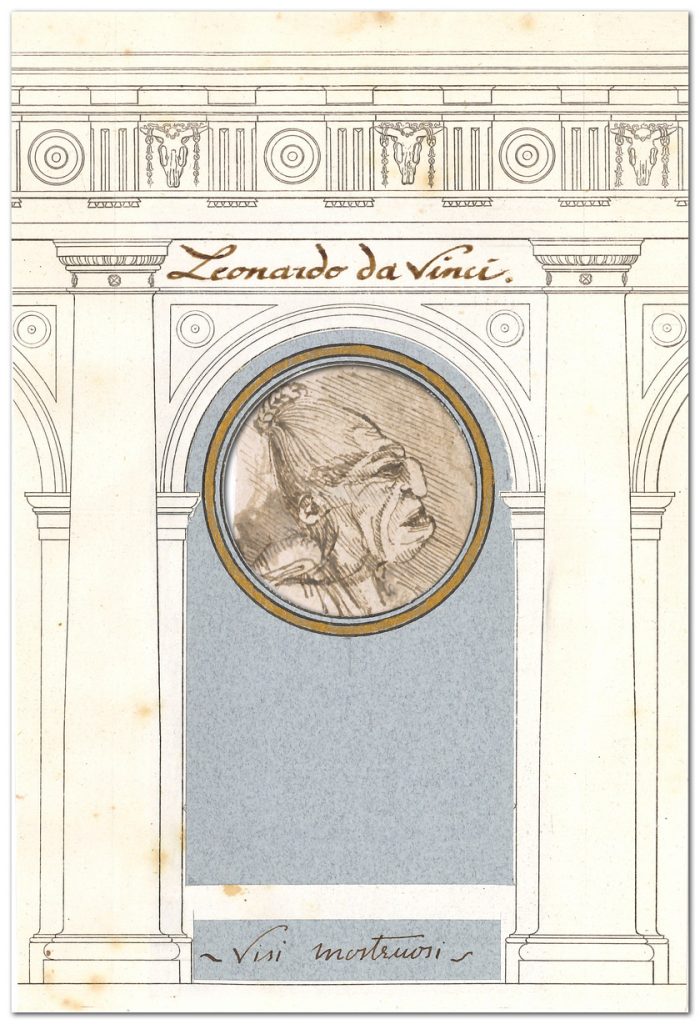

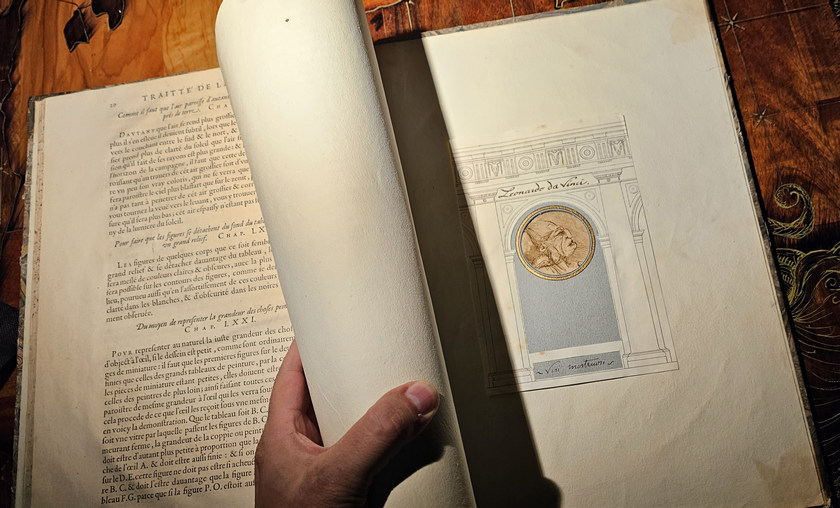

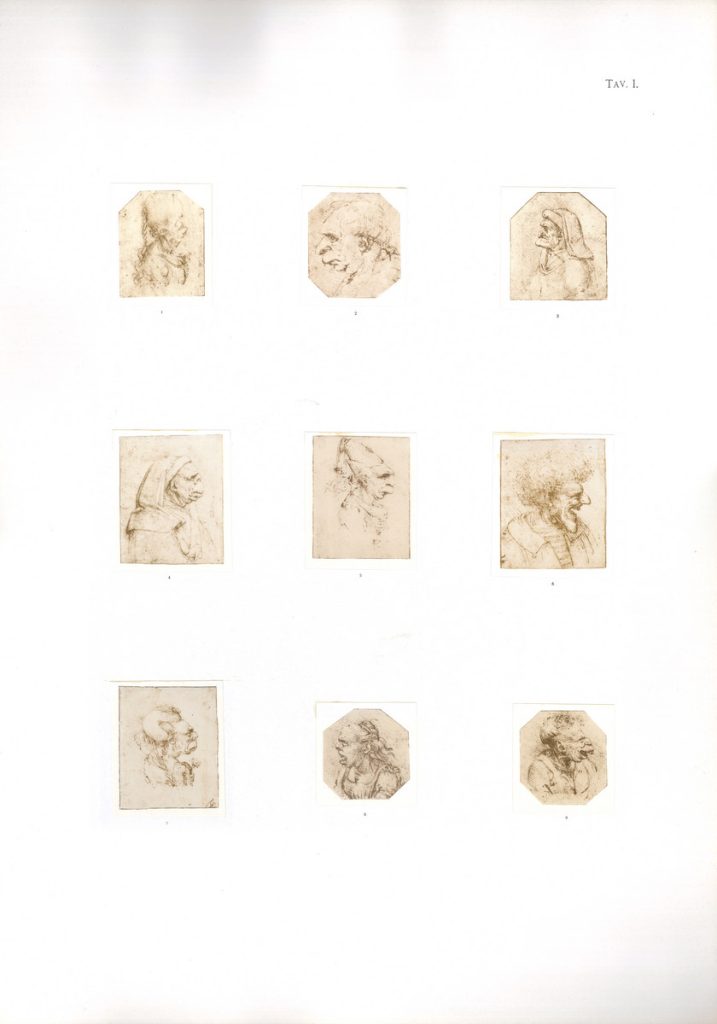

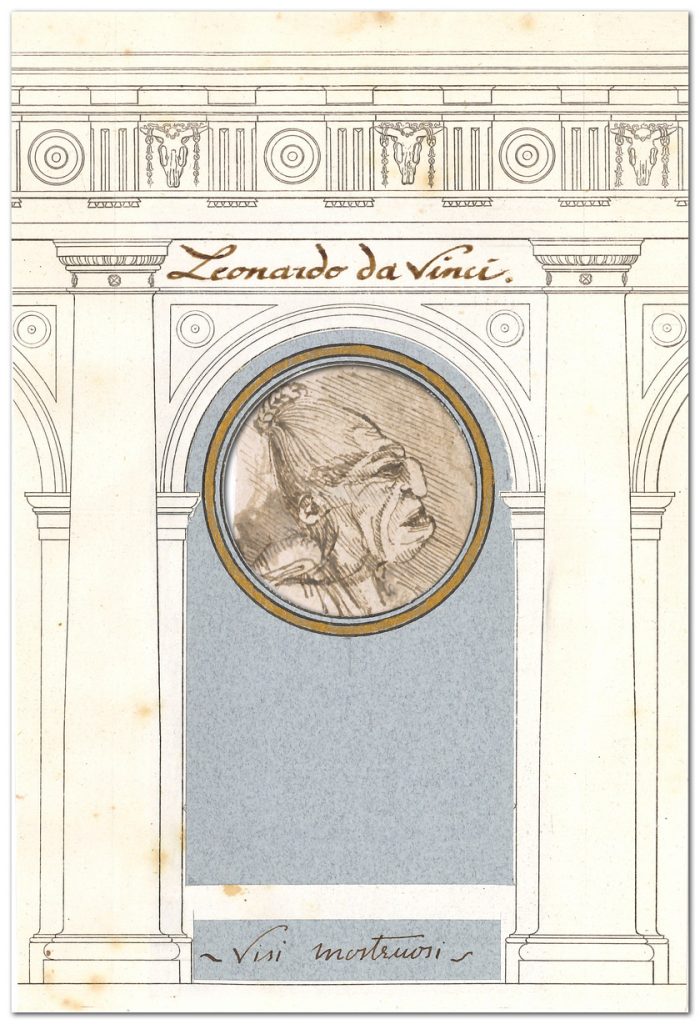

~ Visi mostruosi, volto di Megera ~

1490 / 1510 circa

Testa caricata e busto di profilo di megera verso destra, 1490 circa

Punta metallica, penna e inchiostro seppia su carta filigranata.

Frammento in carta di stracci (50 x 56 mm) ottagonale

incollato su carta giallastra quadrata

con retro azzurrato 72 × 72 mm,

![]()

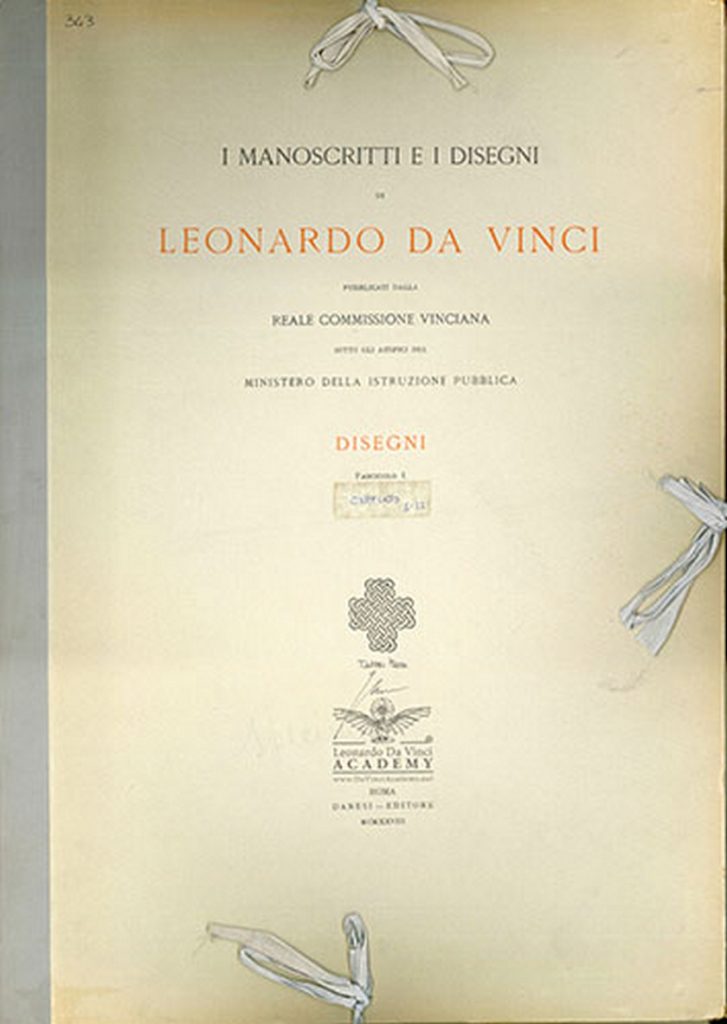

Leonardo da Vinci e i “Visi Mostruosi”: Un Ritrovamento Eccezionale in un’Edizione Rara del Trattato di Pittura

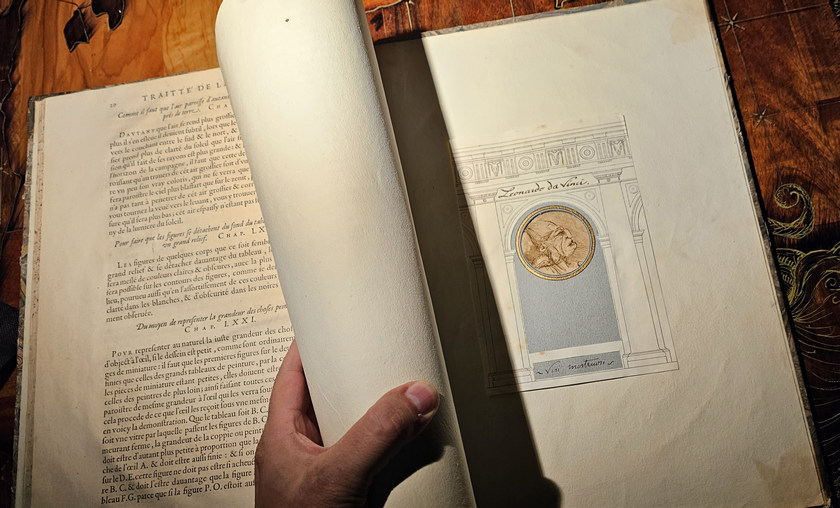

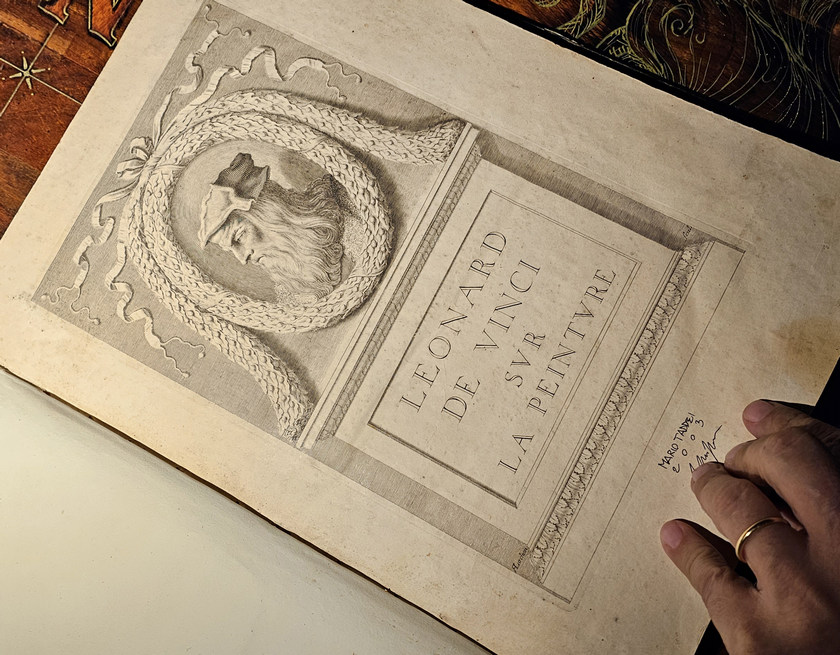

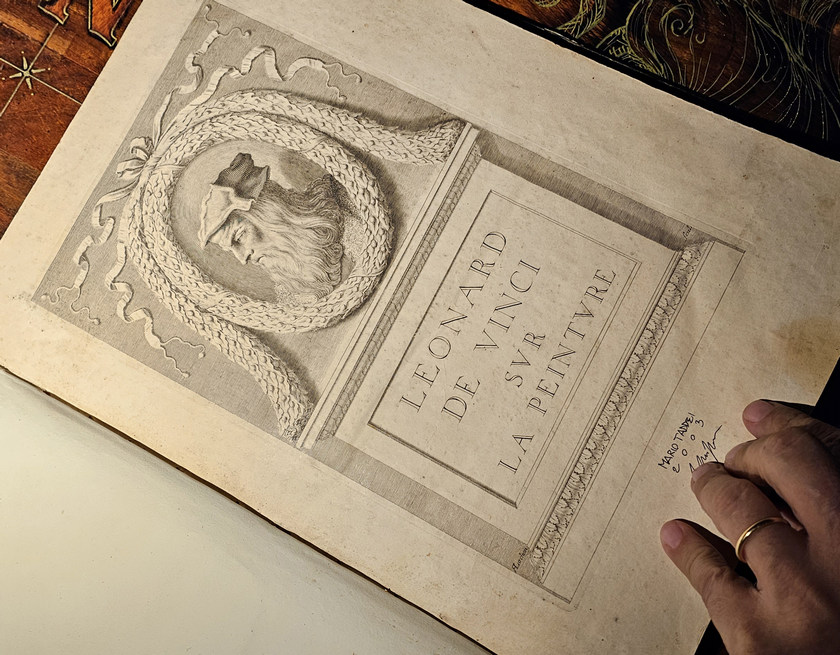

Recentemente, in un’edizione rara del Trattato della Pittura di Leonardo da Vinci, stampata nel 1651 in Francia, è emerso un ritrovamento straordinario che aggiunge un valore inestimabile a questa opera già di per sé preziosa. Nella penultima pagina del volume è stata scoperta una tasca, o passepartout, ricavata da un disegno intitolato “Visi Mostruosi”. Questo disegno è particolarmente significativo poiché all’interno della tasca è custodito un frammento di carta di dimensioni 50×56 mm, incollato su un fondo azzurrato di 72×72 mm. Questo pezzo di carta ottagonale è realizzato con la carta di stracci tipica del Rinascimento, lo stesso materiale utilizzato da Leonardo da Vinci per i suoi appunti e disegni.

Il frammento in questione contiene un disegno realizzato con punta metallica, penna e inchiostro di seppia, che raffigura il profilo di una vecchia caricaturale, simile a una strega o Megera, rivolta verso destra. Questo tipo di rappresentazione rientra nel corpus di opere che Leonardo realizzò tra il 1490 e il 1510, un periodo in cui l’artista era particolarmente affascinato dalla rappresentazione di “visi mostruosi” e caricaturali.

DONNE AU PUBLIC ET TRADUIT D’ITALIEN EN FRANÇAIS

editio princeps – première édition

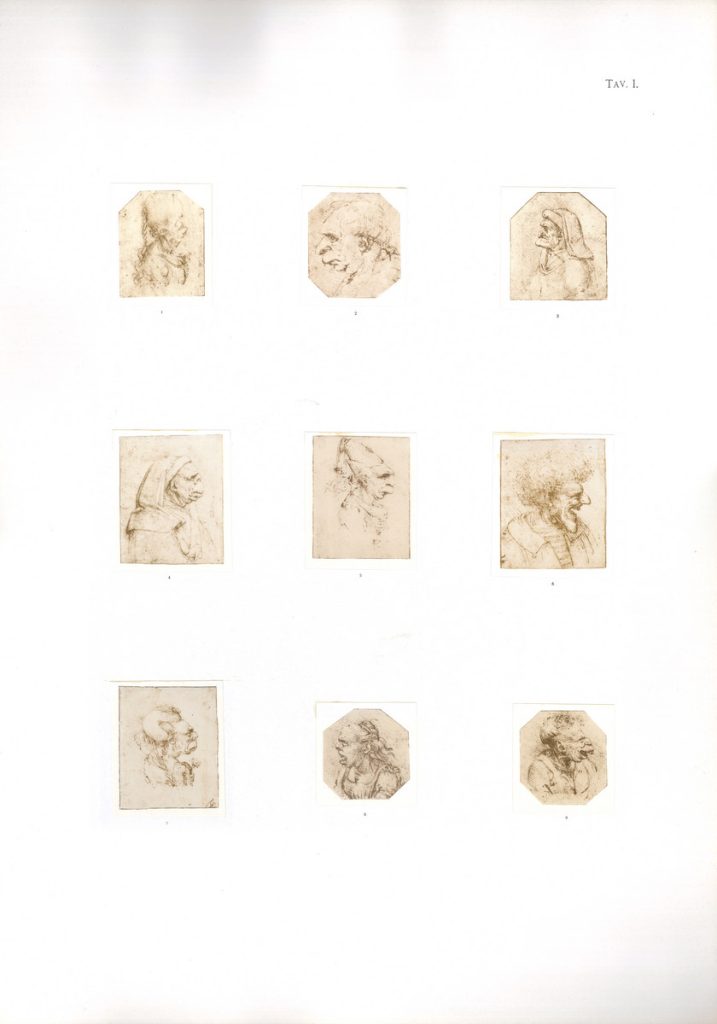

Questi disegni, conservati presso la Biblioteca Ambrosiana di Milano, comprendono una serie di ritratti di giullari di corte, anziani e figure grottesche, spesso con nasi esageratamente pronunciati e smorfie marcate. La loro particolarità non risiede solo nell’aspetto grottesco, ma anche nel profondo interesse di Leonardo per la fisiognomica e la sua ricerca di catturare l’essenza dell’anima umana attraverso il disegno. In effetti, Leonardo stesso scrive nel Codice Madrid II (72v) riguardo alla “varietà dei visi secondo gli accidenti dell’uomo, in fatica e riposo, in ira, in pianto, in riso, in gridare, il timore e simil cose.”

Questa affermazione sottolinea l’intento di Leonardo di esplorare e documentare la vasta gamma di emozioni e stati d’animo umani attraverso l’osservazione meticolosa dei volti. Non è solo l’estetica a interessare l’artista, ma anche la capacità del volto umano di raccontare una storia, di trasmettere emozioni intense e contrastanti.

Un altro riferimento significativo si trova nel Manoscritto A (106v), dove Leonardo menziona i “visi mostruosi”. Egli scrive: “De’ visi mostruosi non parlo, perché sanza fatica si tengano a mente.” Questo passaggio è particolarmente rivelatore, poiché suggerisce che i volti grotteschi e deformi ritratti da Leonardo erano talmente memorabili da non richiedere ulteriori descrizioni o spiegazioni. Erano immagini che, per la loro stranezza e forza espressiva, restavano impresse nella mente senza bisogno di parole. Leonardo sembra quasi voler custodire questi volti come segreti visivi, la cui potenza evocativa supera la necessità di essere narrata.

Biblioteca Leonardo da Vinci ACADEMY

Durante il periodo in cui questi disegni furono realizzati, Leonardo era impegnato nella creazione di L’Ultima Cena nel refettorio del convento di Santa Maria delle Grazie a Milano. Nei suoi scritti, egli narra di come percorresse le strade di Milano alla ricerca di volti che potessero ispirare le figure degli apostoli e di Gesù. Una leggenda narra che Leonardo trovò il volto di Giuda in un uomo dal carattere crudele e che, per una sorta di scherzo, utilizzò il volto del priore del convento, con cui aveva un rapporto conflittuale, per rappresentare il traditore.

Leonardo – CVinciana Tav 212 – Chatsworth – Biblioteca duca di Devonshire –

Biblioteca Leonardo da Vinci ACADEMY

Indipendentemente dalla veridicità di questa leggenda, ciò che è certo è che Leonardo osservava attentamente le persone comuni, ritraendole non solo nei loro tratti fisici, ma anche nella loro essenza interiore. Questa collezione di ritratti grotteschi non rappresenta semplicemente un esercizio di caricatura, ma una profonda esplorazione dell’umanità. Contrariamente ai ritratti idealizzati delle nobili dame, come La Gioconda, La Belle Ferronnière, e La Dama con l’Ermellino, queste rappresentazioni offrono uno sguardo più autentico e realistico sulle persone che popolavano Milano nel 1500.

Leonardo da Vinci ACADEMY

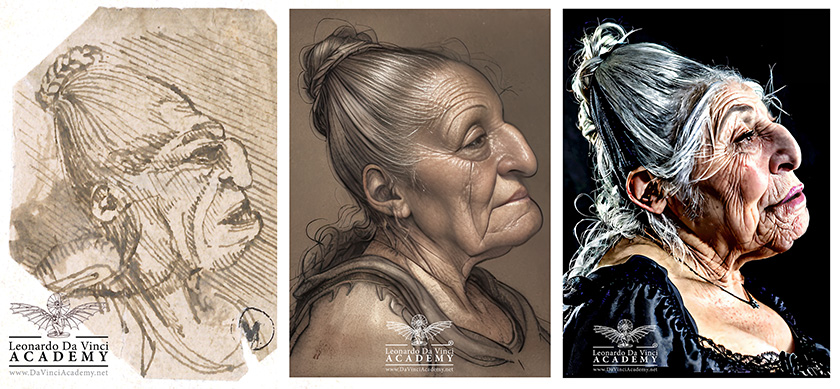

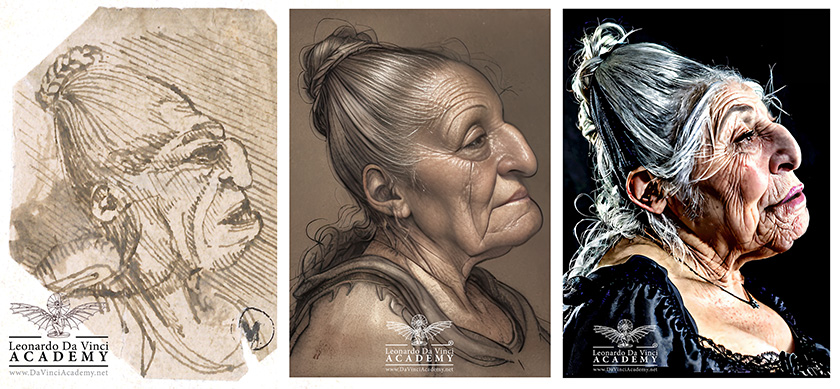

Il frammento ritrovato nell’edizione del 1651 del Trattato della Pittura raffigura uno di questi “visi mostruosi”: il profilo di una vecchia, con un grande naso adunco, capelli raccolti dietro la testa e un mento prominente. Questo disegno, unico nel suo genere, è stato mostrato per la prima volta in televisione in Italia e attualmente appartiene a una collezione privata.

DONNE AU PUBLIC ET TRADUIT D’ITALIEN EN FRANÇAIS

editio princeps – première édition

Questo ritrovamento non solo aggiunge un valore storico e artistico all’edizione del Trattato della Pittura, ma ci offre anche uno spaccato della mente di Leonardo da Vinci, un uomo capace di trovare bellezza anche nei volti più grotteschi, e di vedere l’umanità in tutte le sue forme.

Ricostruzione digitale del volto di Megera

Riferimenti e documenti

“Delle varietà de visi, secondo li acidenti dell’omo, in fatica, in riposo, in ira, in

pianto, in riso, i’ gridare, in timore e ssimili cosse.”

Madrid II 72v

“Del modo di tenere a mente la forma d’un volto.

Se volli avere facilita in tenere a mente una aria d’uno volto, impara prima a

mente di molte teste, occhi, nasi, bocche, menti e gole e colli e spalli. Poniamo caso, i nasi sono di 10 ragioni: diritto, gobbo, cavo, col rilievo più su o più giu che ‘l mezzo, aquilino, pari, simo e tondo e acuto: questi sono boni in quanto al proffilo. In faccia i nasi sono di 11 ragioni: equale, grosso in mezzo, sottile ‘n mezzo, e la punta grossa e sottile nell’appiccatura, sottile nella punta e grosso nell’appiccatura, di larghe anarise, distrette, d’alte e basse, di busi scoperti e di busi occupati dalla punta. E cosi troverai diversita nelle altre articule, delle quali cose tu de’ ritrarre di naturale e metterle a mente, ovvero, quando hai a fare uno volto a mente, porta con teco uno picciolo libretto, dove sieno notate simile fazione e quando hai dato una occhiata al volto della persona che voi ritrarre, guarderai poi in parte quale naso o bocca se le assomiglia, e favvi uno picciolo segno per riconoscerle poi a casa. De’ visi mostruosi non parlo, perché sanza fatica si tengano a mente.”

Manoscritto A 106v

Riportato poi nel Trattato di Pittura

Libro di Pittura (Codice Urbinate Lat. 1270) Capitolo 290

ENGLISH

Leonardo da Vinci and his “Monstrous Faces”: An Extraordinary Find in a Rare Edition of the Treatise on Painting

~ Monstrous faces, face of Megera ~

1490 / 1510 circa

Charged head and profile bust of hag towards right, c. 1490 Metal point, pen and sepia ink on watermarked paper. Rag paper fragment (50 × 56 mm) octagonal pasted on square yellowish paper with blued reverse 72 × 72 mm,

![]()

Leonardo da Vinci and the “Monstrous Faces”: An Exceptional Find in a Rare Edition of the Treatise on Painting

Recently, in a rare edition of Leonardo da Vinci’s Treatise on Painting, printed in 1651 in France, an extraordinary find emerged that adds priceless value to this already valuable work. On the penultimate page of the volume, a pocket, or passepartout, was discovered from a drawing entitled “Monstrous Faces.” This drawing is particularly significant because inside the pocket is housed a 50×56 mm fragment of paper, glued to a 72×72 mm blued background. This octagonal piece of paper is made from the rag paper typical of the Renaissance, the same material used by Leonardo da Vinci for his notes and drawings.

The fragment in question contains a drawing made with metal point, pen and sepia ink, depicting the profile of a caricatured old woman, resembling a witch or Megera, facing to the right. This type of depiction is part of the body of work that Leonardo produced between 1490 and 1510, a period when the artist was particularly fascinated by the depiction of “monstrous faces” and caricatures.

DONNE AU PUBLIC ET TRADUIT D’ITALIEN EN FRANÇAIS

editio princeps – première édition

These drawings, preserved in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, include a series of portraits of court jesters, old men and grotesque figures, often with exaggeratedly pronounced noses and marked grimaces. Their uniqueness lies not only in their grotesque appearance, but also in Leonardo’s deep interest in physiognomy and his quest to capture the essence of the human soul through drawing. Indeed, Leonardo himself writes in Codex Madrid II (72v) about the “variety of faces according to the accidents of man, in toil and rest, in wrath, in weeping, in laughter, in crying, fear and simil things.”

This statement underscores Leonardo’s intent to explore and document the wide range of human emotions and moods through meticulous observation of faces. It is not only aesthetics that interested the artist, but also the ability of the human face to tell a story, to convey intense and conflicting emotions.

Another significant reference is found in Manuscript A (106v), where Leonardo mentions “monstrous faces.” He writes, “De’ visi monruosi non parlo, perché sanza fatica si tengono a mente.” This passage is particularly revealing because it suggests that the grotesque and deformed faces portrayed by Leonardo were so memorable that they required no further description or explanation. They were images that, because of their strangeness and expressive force, stuck in the mind without the need for words. Leonardo seems almost to want to guard these faces as visual secrets whose evocative power surpasses the need to be told.

Leonardo da Vinci ACADEMY Library.

During the period when these drawings were made, Leonardo was busy creating The Last Supper in the refectory of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. In his writings, he recounts how he walked the streets of Milan looking for faces that could inspire the figures of the apostles and Jesus. One legend has it that Leonardo found the face of Judas in a man with a cruel character and that, as a sort of joke, he used the face of the prior of the convent, with whom he had a contentious relationship, to represent the traitor.

Leonardo – CVinciana Tav 212 – Chatsworth – Duke of Devonshire Library – Leonardo da Vinci ACADEMY Library

Regardless of the veracity of this legend, what is certain is that Leonardo carefully observed ordinary people, portraying them not only in their physical features but also in their inner essence. This collection of grotesque portraits is not simply an exercise in caricature, but a profound exploration of humanity. In contrast to the idealized portraits of noble ladies, such as La Gioconda, La Belle Ferronnière, and The Lady with an Ermine, these depictions offer a more authentic and realistic look at the people who populated Milan in the 1500s.

The fragment found in the 1651 edition of the Treatise on Painting depicts one of these “monstrous faces”: the profile of an old woman, with a large hooked nose, hair pulled back behind her head, and a prominent chin. This unique drawing was first shown on television in Italy and currently belongs to a private collection.

DONNE AU PUBLIC ET TRADUIT D’ITALIEN EN FRANÇAIS

editio princeps – première édition

This finding not only adds historical and artistic value to the edition of the Treatise on Painting, but also gives us a glimpse into the mind of Leonardo da Vinci, a man capable of finding beauty even in the most grotesque faces, and of seeing humanity in all its forms.

Digital reconstruction of the face of Megera

References and documents

“Delle varietà de visi, secondo li acidenti dell’omo, in fatica, in riposo, in ira, in

pianto, in riso, i’ gridare, in timore e ssimili cosse.”

“Of the varieties of faces, according to the acidents of the man, in toil, in rest, in wrath, in weeping, in laughter, i’ shouting, in fear and same things”

Madrid II 72v

“Del modo di tenere a mente la forma d’un volto.

Se volli avere facilita in tenere a mente una aria d’uno volto, impara prima a mente di molte teste, occhi, nasi, bocche, menti e gole e colli e spalli.

Poniamo caso, i nasi sono di 10 ragioni: diritto, gobbo, cavo, col rilievo più su o più giu che ‘l mezzo, aquilino, pari, simo e tondo e acuto: questi sono boni in quanto al proffilo. In faccia i nasi sono di 11 ragioni: equale, grosso in mezzo, sottile ‘n mezzo, e la punta grossa e sottile nell’appiccatura, sottile nella punta e grosso nell’appiccatura, di larghe anarise, distrette, d’alte e basse, di busi scoperti e di busi occupati dalla punta. E cosi troverai diversita nelle altre particule, delle quali cose tu de’ ritrarre di naturale e metterle a mente, ovvero,

quando hai a fare uno volto a mente, porta con teco uno picciolo libretto, dove sieno notate simile fazione e quando hai dato una occhiata al volto della persona che voi ritrarre, guarderai poi in parte quale naso o bocca se le assomiglia, e favvi uno picciolo segno per riconoscerle poi a casa. De’ visi mostruosi non parlo, perché sanza fatica si tengano a mente.”

“Of the way of keeping in mind the form of a face.

If I wished to have facility in keeping in mind an air of a face, first learn in mind of many heads, eyes, noses, mouths, chins and throats and necks and shoulders. Let us say, the noses are of 10 reasons: straight, humped, hollow, with the relief more up or more down than ‘the middle, aquiline, even, simo and round and acute: these are good as to the proffile. In the face the noses are of 11 reasons: equal, coarse in the middle, thin in the middle, and the tip coarse and thin in the sticking, thin in the tip and coarse in the sticking, of broad anarise, distracted, of high and low, of uncovered busi and of busi occupied by the tip. And so you will find diversities in the other particulae, of which things you de’ portray naturally and put them in mind, or, when you have to make a face in mind, bring with you a little booklet, wherein similar factions are noted, and when you have taken a look at the face of the person whom you portray, you will then look in part what nose or mouth if it resembles them, and favvi a little mark to recognize them afterwards at home. Of monstrous faces I speak not, that without effort they may be kept in mind.”

Manuscript A 106v

Later reproduced in the Treatise on Painting Book of Painting

(Urbinate Codex Lat. 1270) Chapter 290